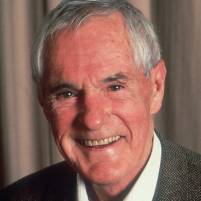

INTERVIEW WITH

TIMOTHY LEARY

INTERVIEW WITH

TIMOTHY LEARY

By Marianne Schnall (1994)

I was born in 1967, too young to appreciate the psychedelic Sixties of hippie love-ins and flower power. In fact, the first time I ever heard of Timothy Leary was as a child singing along to the soundtrack of Hair. In 1989 I learned of his psychedelic research at Harvard while I was an undergraduate at Cornell University. Four years later, in 1993, I had the good fortune of actually meeting the world-famous psychologist at a press party thrown in his honor at a trendy New York restaurant. He kindly invited me to a lecture he was giving the next day on Virtual Reality. The talk was fascinating. Dr. Leary was a powerfully charged and spellbinding speaker who reached people on many levels.

A few weeks later, I called him at his house in Beverly Hills. He said he would call me back to schedule an interview and I spent the next two days waiting by the phone, snowed in, reading his historic autobiography, Flashbacks. His book is entertainingly provocative and offers insights into the psyche of a legend. His story is one of resilience and a commitment to truth. He challenged conventional wisdom with his controversial ideologies and experiments devised to expand consciousness, spearheading a psychedelic revolution. Later, he became a political prisoner, ending up in jail for four years for possession of a small amount of marijuana. It was there that he wrote one of his most acclaimed books about the Eight Circuit Model of the Brain. Forty years later, his Harvard research into psychedelic drugs is being updated and continued. He has been honored for his past work with two national awards, from the American Association of Psychology and the American Humanist Psychological Association.

By the time he called me I was eager with anticipation of our conversation. Throughout the interview he was sharp, high-energy and electrifyingly eloquent. His knowledge is vast and diverse – he wears hundreds of hats, among them those of revolutionary, satirist, modern-day philosopher, computer pioneer, impassioned humanist and distinguished psychologist. He is also prone to sudden, emotionally charged asides, as when he stops to condemn “the relentless, ruthless repression of women and children by men” or to stress his catch sayings like “Question authority” and “D.I.Y. – do it yourself.” Despite a celebrated life, he was a genuinely humble man – a visionary with a big heart who has dedicated his life to the cause of personal liberation and the empowering of the individual. His prolific scholarly output and urgent empirical findings continue to advance the frontiers of the human experience.

Note: Two years after this interview, on May 31st, 1996, on a full moon just slightly after midnight, Dr. Timothy Leary died in his sleep surrounded by friends at his mountaintop home in Beverly Hills. He was seventy-five and died from inoperable prostrate cancer, and according to his son Zachary, his last words were, "Why not?" and "Yeah." A cyber-memorial took place at his site on the World Wide Web (https://www.leary.com), where he had posted health updates and described the process of "designer dying", which included his daily intake of both legal and illegal drugs. His last book "Design for Dying" explored his experience and offers, in his words, “ common-sense, easy-to-understand options for dealing planfully, playfully, compassionately, and elegantly with the inevitable final scene .” Leary, always an iconoclast, had originally planned to capture his final moments on videotape for possible broadcast on the Internet, and arranged in advance of his death to have a portion of his cremated remains sent into space, which they were in April of 1997, alongside those of “Star Trek” creator Gene Roddenberry.

Rather than mourn his passing, Tim would have wanted us to celebrate his life, and continue to ponder and learn from all the wealth of research, insights and wisdom he left with us. It is in that spirit that I share this interview, portions of which originally appeared in Ocean Drive Magazine in 1994. His observations are certainly as potent and relevant today as they were when this interview was first conducted. But that should be no surprise since Timothy Leary was always ahead of his time.

Marianne Schnall: You’ve had an incredible career. How would you describe your work?

Timothy Leary: My profession is I’m a dissident philosopher. I’m from the school of Socrates – it’s humanism – the Socratic methods which appeared in Greece over 2,000 years ago, it reappeared as the romantic movement in the eighteenth century – it’s the same movement. It’s called humanism, and its motto is “Think for yourself,” “Question authority” and, as Socrates said, “Know thyself.” The aim of human life is to develop yourself as a philosopher, and it goes along with what’s known as paganism or pantheism or polytheism – that divinity, the divine intelligence – is found within, and is not to be found in institutions. I have one further thing to say about this. This philosophy, which is over 5,000 years old, was assimilated and streamed through the Ganges 4,000 years ago and is the basis of Buddhism, it’s the basis of Taoism in China, it’s the basis of mystical Christianity and Islam – it’s that basically, the interest is Chaos. From the standpoint of a human being, you can’t figure it out and you should avoid people who try to give you rules and regulations and laws, because the laws they’re imposing on you are simply local ordinances to benefit themselves. So that this school of philosophy has always been irreverent, it’s always been outsider, it’s always been dissident and in my life I’ve been lucky enough to have lived through four stages of humanism all based on new media, new forms of communication which have changed our culture. Now we’ve set up this background of what I’m doing in the context that it’s been done throughout all of human history. And it’s called humanism.

MS: So you would consider yourself to be a humanist psychologist?

TL: In the 1950s, when I was at U.C. Berkeley, I was one of a small group of psychologists to develop what’s known as a humanist psychology. And our aim, being good Socratic boy scouts, was to undermine authority, so we tried to take the power of the diagnosing and treating of behavior away from the doctors and give it back to the individuals. This was called “group therapy.” I was involved in the early years of Alcoholics Anonymous. I was very active in the “do it yourself” group movement, which has developed sensitivities into what is now almost taken for granted. Now the key here is D.I.Y. – do it yourself. And back in the Fifties we were telling people don’t rush off to a doctor to be diagnosed or by an analyst – do it yourself. And also do it within small groups of friends. Philosophy is a performance sport – you have to play it with somebody back and forth. By the way, this was tremendously successful, I wrote two best selling books and my tests were used by over 800 clinics.

MS: Haven’t those same tests been utilized at penal institutions?

TL: Yeah, I had to do my own tests when I went to prison later on. Then in about 1960 I was asked to come to Harvard to institute new methods. At that time I was introduced to the psychedelic mushrooms of Mexico and basically the concept that you could expand consciousness and learn how to operate your brain and learn how to become a wiser person through the careful, well prepared use of psychoactive vegetables. It was the same method – D.I.Y. – so we took the power of medicine away from the doctors, because just at the time, in the mid-Fifties and early Sixties, when we started our work at Harvard, that’s when the tranquilizers had been developed. Valium and Thorazine and the Miltown and it was a CRAZE – doctors were running around writing prescriptions, drugging people with these tranquilizers. We were all very much against that. We felt if anyone’s going to drug you, you do it yourself and you do it with friends and you do it in the classic shamanic tradition. So we started at Harvard a research group which was soon known as The Psychedelic Research Project. Richard Alpert – Baba Ram Dass – was one of the co-directors, Frank Barron from U.C. Santa Cruz was one, I was the co-director, and over about four years, about 40 well-known successful professors, grad students, doctors, practitioners joined us there, including people like Aldous Huxley and Gerald Heard.

MS: I was curious how you felt about the wide-spread use of the new psychoactive drugs, such as Prozac, for treating conditions other than depression – just for a sort of pick-me-up.

TL: Now remember in the Fifties we wanted to take the power of diagnosis and treatment away from the medics and put it in the hands of people. In the Fifties and Sixties we took the power monopoly of psychoactive drugs away from the doctors. Yes, I totally deplore the notion of an MD giving pills to patients – a medical doctor giving psychological or psychoactive change agents to another person. This is almost mechanical, it’s factory like. To say that there is a cure for something like depression – well, for instance – one of the things that has run through all my work, and is quite important and I think easy to understand, is that we don’t categorize human beings or human behavior. We quantify or dimensionalize. See, what they say is you’re a hysterical, you’re a schizophrenic, you’re a paranoid – these are labels, they’re codes, which of course comes basically from religion. Instead, we develop methods of dimensionalizing. “On a rating scale of one to ten, how depressed are you?” “Well, Jesus, I’m nine right now, but last Tuesday night I was up there with a two.” In other words, when you dimensionalize a human behavior it’s no longer a branded label on your forehead that you’re a Jew or a Christian or a hysteric or an anal – You see, we all have these categories or behaviors that we can change and we can compare with each other and they’re not final products. I still oppose the MDs passing out psychoactive drugs to patients and treating them like helpless victims. “Here, open your mouth and let Big Daddy give you a pill.”

MS: How do you feel about the government’s involvement with drug legalization?

TL: In no way do I want drugs legalized by the government. Who are these bureaucrats, corrupt scoundrels in Washington, who think that they can legalize personal behavior of adults, of what I put in my body, or what I drink, or what my wife and I do about birth control, what my wife does about abortion – these are personal rights the government cannot decriminalize. They have no right. The last thing in the world I want is government bureaucrats also giving authorized drugs, even drugs like LSD and marijuana, to patients. These are decisions that have to be made by individuals or individuals in small groups or by wise and experienced human beings called shamans, who are just people who know the score. These are the people who can help you and counsel and guide you.

MS: You lecture at colleges all over the country. What are your impressions of young people today, growing up in the age of computers?

TL: You notice one thing about the new generation of kids, the high tech kids: They all have beepers and they can master any kind of computer – there’s never been a generation that is more body-conscious. They have tattoos, they have piercings, they have rings – they’re using their bodies as forms of communication and decoration. And God knows, they’re healthier. They’re running around – young women are running around like track stars. And when people criticize the computer generation, the high tech generation, and say they neglect the body – well, just walk through a college campus and you’ll see the healthiest, most physically conscious and alert group of human beings I’ve ever met. So they’re not nerds at all.

MS: When did you begin working with computer linguistics and digital thought?

TL: Well, number one, I want to point out that I was one of the first psychologists to use computers way back in the late seventies. Early fifties, we were using main frame computers to get our scores which we then put on the bulletin board so patients could see how their scores compared with each other. I've always been involved in digitizing and score keeping as a way of understanding yourself and others. In the 1980's, of course, an incredible event happened which changed American culture - a new media developed. Radio developed as a new media in the twenties and created the jazz age and created a changed America and of course television changed America by bringing the world into our living room. But it was all passive. The problem with the sixties, the problem with most hippies, the problem with television watching, is it's passive consumption. You're sitting there, you have the choice of selecting your cables or your dials or channels. But in the 1980's an incredible technological advance happened in media - computers - YOU could change what's on your screen. And it's interesting, it's always young people that like and can use the new medium, because old people are stuck - you know, my mother and father never really liked television, they were stuck on radio. I really had to be taught by my grandchildren about computers because they were so far ahead of me.

MS: What are the implications of electronic communication?

TL: Since the 1980's, there's been a new way of communicating thoughts, a new language developing. It's called digital, or now, it's called multimedia. And the idea is instead of just using a telephone to send messages at the speed of light sound, you can edit in your own home appliance, your own multimedia message and send it at the speed of light, in glorious Technicolor and sound, to people around the world. And when I say that, sometimes people think that I'm hallucinating a bit. "What's this - there's going to be a new form of communication which will take the place of ABC and NBC and all that?" The fact is, as you probably know Marianne, is that right now, there's something like twelve million people who have modem systems and belong to electronic bulletin boards. In other words, they already belong to communities, to committees, to clubs, which they get on-line and share ideas with people from different countries. So this new culture is very much tied to my original idea of taking therapy away from the doctors and taking the drug power monopoly away from the doctors. Now we're taking the monopoly of ABC and NBC away from the big shots and we're building software that will allow a ten or twelve-year-old kid to edit their own multimedia audio visual self.

MS: Is cyberspace, in some ways, a type of man-made drug? It sounds like a behavior that could become addictive.

TL: Well, first of all let me examine what you just said. You implied that drugs were addictive. See, all psychedelics drugs are non-addictive. Marijuana doesn't addict you. LSD doesn't. Psilocybin doesn't. Cocaine can become addictive. Alcohol can be. No, it is possible that many people will get addicted to making pictures on screens but as long as they're sending them to somebody else . . . The horrible thing about addiction, no matter whether it's drug addiction or an addiction to television or whatever it is - that it's a lonely thing. You're doing it by yourself. And the key to the cybernetic communication is you're communicating with other people. You're sharing your cybernetic visions with other people. There are like two million bulletin boards out there right now and within two or three years, they'll not just be using letters, they'll be using images - multimedia film clips. It's like advertisers now who jam into thirty seconds a lot of information. We'll all be doing that within five years.

MS: Let me just play devil's advocate for a second. What about concerns about that resulting in social isolation, with people not interacting with our people, but with a computer? Do you think those concerns are valid?

TL: No. Of course, there always will be some loners who like to do this. Addicts are people who can't deal with other human beings. But, think of the telephone. The telephone does not isolate you. As a matter of fact the telephone is an instrument of communication. You know, they told Gutenberg, "Hey, Gutenberg your book is going to make us all into introverts who spend all of our time home reading." But that's not true. You read a book and you want to run out and talk about it and find someone else who's read the book. No, the aim of all of this technology is to allow people to communicate. We call it interpersonal - not interactive - interpersonal - to communicate with each other at higher levels of acceleration and variety. And one important thing is a new language is developing. It's already developing. It's the global language. It does not depend on A-B-C or C-A-T or D-O-T. It's going to be a global language, which is going to do a tremendous amount to bring the different countries, the different races, the different religious groups together in what Marshall McLuhan called the global village. By the way, McLuhan is the father, the prophet, the key person, to figure this all out in the fifties.

MS: How can you measure and modify behavior with computer software, as in the program you designed, "Mind Mirror"?

TL: Yes, many people see all this in a psychotherapeutic sense and that's not true at all. We're talking about a new form of communication that will empower you. Like, books don't cure, books allow people to communicate more effectively. See, the logic there? Computers and computer programs are not going to cure, they're not supposed to be used by doctors to play electronic games with people. They put individuals in touch with each other - to share viewpoints, to share experiences. There is always this notion that drugs are supposed to be . . . See, I believe very much in antibiotics. I had pneumonia over the weekend and I am very grateful to my wonderful doctor to give me antibiotics. So I do believe in the use of drugs for the body. But you simply cannot use drugs to change the mind because then you're getting into addiction or you're getting into a set of thinking you're being drugged.

MS: I really enjoyed your lecture on virtual reality. How is virtual reality going to change the landscape of the human experience?

TL: Well, the word virtual reality has many different meanings. It basically means electronic realities. And it means that we're developing very inexpensive equipment that will allow you to have goggles that you can wear just like two television screens, so you're actually kind of walking around immersed in an electronic environment. So, when you think of virtual reality, think of immersive realities in which you can move through the rooms and the halls of an electronic house. You can click on electronic books and open them up. You can click on paintings and you can go through the Louvre. It's simply the use of electronic realities. The nice thing about it is, you see, you can design your own realities and you can invite other people around. Within three or four years - even right now, some kids are doing it - but within two or three years, your average kid in America or Japan will be designing their own little homes. And you'll click through telephone, you'll modem over and you'll be in the person's home, and the person will say, "Hey, look at this new painting I have!" Click. Or "Hey, I've got my friend here Joe from Tokyo." Click. "Talk to Joe."

MS: I understand you became involved for a while with the rave movement.

TL: Well, the rave movement, it doesn’t even exist anymore. It was a fad. It was like disco, you know? It was fun while it lasted. But the notion of using this imagery, exists and a new language will come from that.

MS: You’re also a well known advocate for space migration. What ideas do you have for a future evolution where families migrate in space?

TL: Well, in the 1970s there was a big civilian movement for space migration. What happened was that in 1980 Ronald Reagan took NASA over and made it very military and Star Wars. Since that time, cyberspace is taking the place of intergalactic space. We are going to migrate from the planet, I have no doubt about that, but it’s not going to happen as soon as we had hoped. And in the meantime, the way to get ready for this is build up communities of people from different countries who share cyberspace. It’s a very interesting comment that they call it cyberspace. In other words, this new electronic environment that you can visit, which in some ways is analogous to going out into real space out there in Jupiter and Mars – they call it cyberspace. This is a very interesting metaphor.

MS: There’s been a recent resurgence of interest in your research from the Sixties. They’re presently looking into the effects of using mescaline and LSD in disciplining hardened criminals in jail. Can psychedelics be used to re-imprint violent or antisocial behavior?

TL: Yes, in the years 1960-63, we had a project at Harvard in which about forty scientists and divinity professors worked to study the effects of psychedelic drugs like LSD and Psilocybin. And one of our major projects was in a prison there. And there’s never been a group of human beings that were told more about the experiment – we actually shared the experience with them. They ended up acting as kind of leaders for other people doing it. It was a model of democratic humanist research. And it really worked. The recidivism rate at the prison went way down. Just in the last two years they’ve done follow-up studies of the prisoners and the results were quite promising. Now, it’s interesting, because exactly at this moment in American history, everyone agrees that the number-one problem is crime and we have to have more prisons to lock up more prisoners. At the present time America has more prisoners than any country in the world. And every politician is saying, “We want more prisons, more prisons, more prisons.” And here we have this research that was done by a group of about thirty Harvard academicians back about thirty years ago, demonstrating that it is very possible to cut down the recidivism rate, to retrain prisoners so that they can have a constructive and productive life. It’s all there in the results of the Harvard prison study. Yes, I would say that the number-one problem today is that we’re imprisoning more and more of our young people instead of educating them. The methods we developed at Harvard in the Seventies certainly deserve to be studied and examined and possibly completed – of course, the key to what we did was not the drugs. The key was sharing the experiences together. It was not a magical drug that we just went in and dropped LSD in their coffee. It was building up an attitude, a climate, a social environment of people that respected each other. And the prisoner’s policy was founded and we did cut the crime rate down. Back in the Sixties, it was so innocent compared to the Eighties. I certainly would urge the prison system and the justice department to re-examine the studies done using psychoactive drugs, with prisoners, in fully informed situations. Not where they’re just doping them in secrecy.

MS: How do you feel about your own time as a political prisoner?

TL: Well, I learned a lot. My task is to learn wherever I find myself with an opportunity to learn a lot, and I certainly learned a lot from prison. In a way, you never really understand politics unless you’ve logged a little time in prison as a political prisoner. I was in prison for my ideas and I learned a lot and I’m very grateful to the American government to give me a four-year scholarship, full-paid with board and room.

MS: You just recently received acclaim for some of the diagnostic work that you did in the Fifties. Have you ever been concerned with being pigeonholed as the “acid guru”?

TL: Yes, it’s very interesting. In the last six months four psychological groups, including the American Association of Psychology, the American Humanist Psychological Association – these are the national groups – and two local groups have honored my work back then. Yeah, if you live long enough and you try to do good…. You know, sometimes I think that no good deed goes unpunished. But that’s not true. Every new generation comes along and reviews the evidence and I’m delighted that a new generation of psychologists is beginning to use the work we did back then and improve on it.

MS: Are there any misconceptions about yourself that you’d like to diffuse?

TL: Well, I don’t know – everyone has their own conceptions. I am a dissident philosopher of the school of Socrates and my aim is to encourage and empower people to think for themselves and question authority and to find the divinity within. That’s classic Emerson. It’s classic William James, it’s classic Hinduism, it’s classic Quantum Physics. And I’m a very, very conventional humanist scientist.

MS: How do you feel about people who see you as a kind of spiritual leader or futurist guru?

TL: I never was a guru – I hate the idea of a guru. I don’t want to master, I don’t want to have to have any power over anybody else. I’ve never put myself in a position of pretending to be a know-it-all. Socrates’ technique is to ask questions, ask questions, ask questions. When I have an interview or when I’m with somebody I try to learn as much as they do, because continual learning is the name of the game. So, no, I don’t think of myself as a guru and if anyone calls me a guru I just kind of laugh. Because they missed the point.

MS: Where do you think the human race is as far as its evolution and potential in understanding the nature of its own consciousness?

TL: For about 25,000 years our means of communication was fire; that is, actual fire itself and its ashes and then the metal and then it’s candles, even the use of engines to create books – steam engines and all that. In the last seventy years a new form of communication has developed called electricity. Electricity has given us radio, it’s given us telephone, it has given us the television. It’s given us an enormous amount of cable access. It has now finally given us digitized appliances so that we can actually change what’s on our screen so we can communicate not in written words, not in rag and glue pages, but we communicate in the language of the galaxy, which is electronics, electric. And this is going to create within ten years – it’s already happening – a new global village. And the young kids that are growing up now using Nintendo, using Macs, using the new editing equipment, they are a different species than those of us who grew up using reading and writing and radio. So I’m extremely, extremely hopeful to see there’s this new generation that is learning a new language, they’re a new breed.

MS: On the other end of the spectrum, is the world experiencing a crisis?

TL: Now, I must say that at the same time, I’m seventy-three years old now, and I’ve watched very carefully, I study what goes on, I read a lot of books and magazines – it’s obvious that civilization is collapsing. Back in 1986, for a whole year my lectures were “Millennium Madness,” and I predicted that it was going to get worse. That the structures, the systems, the politics, the religious structures of the past simply weren’t working. And they were going to crumble and there was going to be a period of terror because when your solid reality of Newton or the Ten Commandments begins to crumble or dissolve, there’s panic. You want order. We all want order. We’re afraid of facing the actual naked truth of the matter, which is that the universe is, for at least species like ours, a very mysterious, highly complex form of chaos. That doesn’t mean that you have to just get down on your knees and worship any person that comes along – it’s a challenge. One thing you can do is deal with other people who share your beliefs and I have a total, total optimistic confidence in the human spirit – humanity when it’s freed. We want to look in each other’s eyes. We want to activate our own brain. We want to be able to communicate. Basically, I think the spirit is there and you’re going to see it in the younger generation in the next ten years and I think that the year 2000 is going to be a really celebratory moment.

MS: When you look out at the world, what practices or behaviors do you see as particularly problematic?

TL: I must conclude by saying the most important thing that I have to say today, I end up every lecture, every performance, every talk with this point. That for the last 25,000 years the number-one problem facing our species has been the relentless, ruthless, brutal repression of women and children by men. I’d say seventy percent of the children born on this planet right now are put into slavery immediately – economic slavery and of course, psychological slavery. And it’s depressing, it’s discouraging – but the glorious thing that’s happening is that for the first time we’re becoming aware of this dehumanization of women and children by men and by our men. You look at newspaper pictures, you look at television, it’s all these big fat men with coats and ties that are causing all the trouble with their guns. And we’re all becoming aware that there are a lot of problems. Feminism is a very complicated issue. My guru here is Susan Sarandon. I think she’s one of the wisest women that I’ve ever known of our time, and she says over and over again, “I’m not a feminist. I’m a humanist.” And I’ll vote for that and I’ll tattoo that on my forehead.

MS: I appreciate your taking the time to answer my questions.

TL: No one’s ever gotten me going this way. I have to congratulate you. You got me all wound up. Thank you.

This interview originally appeared in Ocean Drive Magazine.

Marianne Schnall is a widely published writer and interviewer. She is also the founder and executive director of Feminist.com and cofounder of EcoMall.com, a website promoting environmentally-friendly living. Her interviews with well-known individuals appear in publications such as O, The Oprah Magazine, Glamour, CNN.com, In Style, The Huffington Post, and many others.

|

|---|

| * * * IN-HOUSE RESOURCES * * * |

|---|